Diversity within a Microcosm: Varieties of Expression in Japanese American Art

The emigration of Japanese to the United States and Hawaii began in the 1860s, and ballooned when the U.S. barred Chinese from entering in 1888. From then until 1920, tens of thousands of Japanese – mostly peasants who were not first-born sons – came to America, leaving behind widespread famine and the threat of conscription in a war against Russia for the promise of a better life in the “Rich Land.”

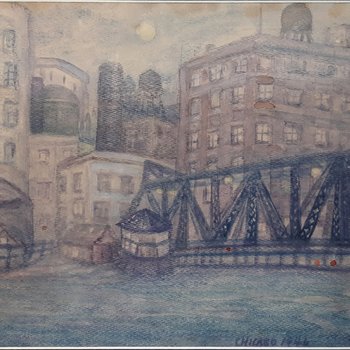

The Japanese (Issei – first generation) and their American children (Nisei – second generation) were a very visible minority. As they attempted to integrate into American society, rural or urban (about 300 Japanese settled in Chicago before the war), racism and prejudice towards the Japanese were the norm.

December 7, 1941 and the war between Japan and the United States of America escalated racism and prejudice into paranoia and a perceived threat to national security. After Pearl Harbor, Chicago Japanese businesses were closed and some Japanese detained in Department of Justice facilities in Chicago. On February 19, 1942, President Franklin D. Roosevelt signed Executive Order 9066, which caused the evacuation and incarceration of 120,000 people of Japanese ancestry, the majority American citizens. Camps were built in the wastelands of Arizona, California, Utah, Idaho, Colorado, Wyoming, and Arkansas, and there most Japanese stayed for the duration of the war.

For those released during the war, Chicago – with its wealth of colleges and job opportunities, and, relatively, higher-level of acceptance of Japanese – was one of the select places where internees came to settle. By the end of the war, Chicago’s Japanese population had grown from a few hundred pre-war to over 20,000. Included in this count were returning Nisei who were stranded in Japan when war broke out, Japanese war brides, and some new immigrants.

The next wave of Japanese immigrants came after the passing of the Immigration and Nationality Act of 1965. They were from all levels of Japanese society, and included professionals, business people and students.

The Japanese population in Chicagoland remains about 20,000 today, with about half tracing their ancestry back to the Issei (now including Sansei, Yonsei and Gosei – 3rd, 4th and 5th generation), and the other half newer immigrants (Shin Issei) and their descendants.

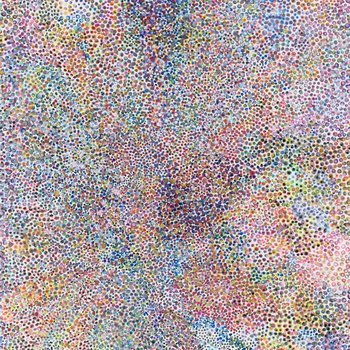

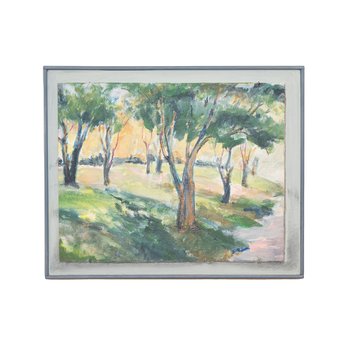

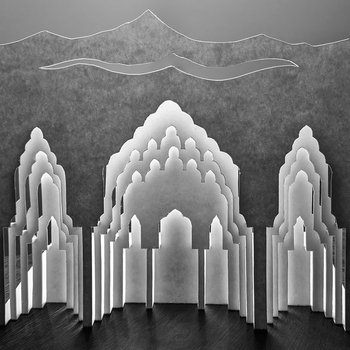

This exhibit is an opportunity to consider artwork by Chicagoans of Japanese descent across generations. Although all the artists share traits based on blood, culture and history, the ways they have expressed themselves is a study in diversity.